- Home

- Celine Roberts

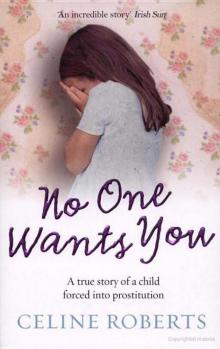

No One Wants You

No One Wants You Read online

Contents

Cover

About the Book

About the Author

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue: My First Communion

1. My Foster Family

2. A Commodity

3. Liberation

4. Safe in Prison

5. Tough Love

6. Daring to Dream

7. New Horizons

8. A Time for Fun

9. Uninvited Guests

10. A Miracle

11. A Place to Call Home

12. Pushing the Odds

13. Maternal Woes

14. The Hunt Begins

15. My Father’s Voice

16. The Royal Visit

17. Sibling Rivalry

18. Buying Acceptance

19. No Celebration

20. Loss of My Life

21. A Soulmate and a Wedding

22. His Departure

23. New Answers

Epilogue: Onwards and Upwards

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Book

Given away by her mother at five months old, raped on the day of her first communion at age seven – when Celine Roberts was told ‘No one wants you’, she believed it.

Illegitimate and unwanted, Celine was forced by her foster mother into prostitution. Her bones were broken, her nose was crushed and she ate candle wax to stay alive.

Celine was finally rescued and sent to an industrial school, where she picked up the pieces of her shattered life. She also began the search for her parents. But what she found gave her battered survival instincts the hardest knock of all …

Full of the most heartbreaking tragedy but ultimately survival and hope, No One Wants You is the remarkably honest and compelling memoir of a woman triumphing over her brutal past.

About the Author

Now in her late fifties, Celine Roberts has recently completed a Masters in Neurology and Rehabilitation at Brookes College, Oxford. She lives in Surrey.

Dedicated to all the silent survivors of abuse

of any kind who feel trapped and unable

to raise their voice in protest.

PROLOGUE

My First Communion

My emotional future was determined by a life-changing event that happened in May 1956. At age seven, I was to make my First Holy Communion.

There was quite a lot of excitement among the children at school in the weeks leading up to this day. Even my foster-mother made sure that I would not miss out on this grand occasion. At least she would be seen by others to be looking after my religious education.

We had to learn certain new prayers. On a practical level, we had to go to the church to practise walking up the aisle, kneeling at the altar rails and sticking out our tongues at the priest, to receive the Communion wafer into our mouths.

Everybody would be dressed up.

There was great talk among the girls about what kind of dress they would wear. Of course all clothing for the day was to be in white. Bearing in mind that my clothes were always second-hand rags and never ever having had a school uniform, I asked my foster-mother with cautious expectation if I would have a white dress. ‘Course ya will, Child, course ya will,’ she assured me in her lilting Cork accent. I didn’t really believe her. I usually had to go and pick up second-hand clothes and shoes for myself from a shop in Limerick. I was afraid to say anything and just prayed that I would get a white dress so that I didn’t look different from all the other girls.

First Communion was to be at early mass on a Sunday morning. After mass we were to go to the school for breakfast and to play among ourselves for a few hours in the schoolyard. I was also looking forward to breakfast as I had heard that we were going to have rashers and sausages. I had never eaten them before but I had smelled them cooking. My foster-mother used to cook them on very rare occasions. They used to smell lovely and my mouth would water when they were frying, but I was never given any to eat. ‘They’d poison ya, Child,’ was what I was told, as she chewed them all up. They were always accompanied by several slices of fried bread, oozing grease that dripped on to her ample bosom.

A few days before Communion Sunday, the parish priest arrived at the house with a large box. I was called in to meet him. He opened the box in front of my foster-mother and myself and took out the most exquisite, spotlessly white Communion dress and head-dress that I had ever seen. He handed it to me.

‘This is from your auntie nuns in Cork,’ he said.

I had no idea what he meant by my ‘auntie nuns’. I did not know any nuns except the teachers at the convent school which I attended on an irregular basis. The remark went right over my head. The dress was brand new. I had never seen anything so beautiful in my life.

‘Is this mine to keep?’

‘This is your First Communion dress. It’s yours.’

I was overcome with excitement. I would have my own new dress for the big day.

Sunday dawned. I was up early and washed in a pan of water from the water barrel, as best I could. The water was freezing and there were insects floating in it. I dried myself off with a rag that was left hanging on a nail in the kitchen. We were fasting before Communion so there was no need for breakfast. My foster-parents stayed in bed.

A pair of white shoes had arrived a day after the dress. They were lovely but they were about two sizes too big for me. I stuffed paper in them to make them fit snugly. I was used to doing this as all my shoes were second-hand and never fitted properly anyway.

When I was dressed, I felt like a princess.

I walked to the church with my foster-mother and when we arrived I joined the other children in the front row of the pews.

The ceremony went according to plan and then we went back to the school where we all had breakfast. I was starving at that stage but I was used to no breakfast. I can still remember how delicious the rashers and sausages tasted. The nuns had laid the table and the hall looked really white and nice, with long tablecloths on all the benches. To this day I love the smell of bacon.

After breakfast it was out to the schoolyard to play. After a couple of hours the bell rang and everyone joined their families who had come to collect them. I remember thinking that everyone else had their father with them, except me. I was told to go home on my own because no one turned up for me. That was normal and I didn’t mind.

It was a two-mile walk home and on the journey I met a number of people. They all said that I looked lovely and a few of them gave me money. One gave me a sixpence. Others gave me a threepenny bit. One man had a camera and asked me to stand beside the gate of his house and he would take my photograph. He said he would give me the print when he had it developed. I was thrilled.

I was so happy by the time I reached home. The sun was shining. It was a lovely day in May. A few of the usual visitors, mainly adult men, had called at the house. There were about three or four of them. I had met two of them when I was out working in the fields, picking potatoes. I didn’t like working with them because they made fun of me and were always poking me. They used to say that I looked like a little tinker. They said that they were calling especially to give me a present of money for my First Communion. Some tried to give me a sixpence or even a shilling, but when my foster-mother saw the coin she berated them into making a larger donation.

‘Ah ya stingy divil ya, give her a half-crown, at least,’ she said, as she stood over them while they dug into their pockets once again.

When they had given the money, which I handed to my foster-mother, out came the bottles of stout. It was to be a party in the middle of the day on a Sunday.

One man told me that he had no present with him. He said that he had half

a crown at home and that I would have to go with him across the fields to get it. I didn’t really want to go but, with my foster-mother’s blessing, I set off with him. He was holding me by the hand as we went across the fields to get my First Holy Communion present.

As we were walking through the fields on that sunny May afternoon to collect the present that he had promised me, he suddenly grabbed me and threw me on the ground.

While he pinned me on the ground, with one hand over my mouth so that I could hardly breathe, he snarled, ‘Ya dirty little tinker ya. Ya won’t need this anymore,’ as he ripped off my Communion dress. His words still haunt me to this very day.

I choked silently as I desperately gasped for air through his rough, foul-smelling fingers. I felt something snap and tried to scream. My hand was killing me. I couldn’t move it. With his one free hand he ripped away my knickers. He then unbuttoned and lowered his trousers. He pulled my legs apart and tried to force something hard inside me. He kept pushing and pushing. It was agony. He was leaning over me and muttering and grunting. I tried to turn off the pain from my lower body. He continued to push into my body, with thrusts. It felt like it went on forever. He eventually collapsed on top of me. He was so heavy.

I went dead inside. I shut down.

I was suffocating.

When he had got his breath back he rose up, fixed his trousers and just walked away in silence.

He just left me there on the ground.

I was seven years old.

I was covered in blood.

Trembling uncontrollably, I made my way home, injured and alone. I could barely stand up. I could only walk a few steps at a time. The pain was excruciating. I was weak from loss of blood and felt dizzy.

I made it as far as the pond where I tried to wash the dirt, the blood and the sticky stuff off me. I was crying because the beautiful First Communion dress sent to me from my auntie nuns was destroyed. It was torn and covered in blood and muck, and I thought my foster-mother was going to kill me.

I stumbled on to the house and tried to open the front door to go in but I was in such shock that I collapsed unconscious on the front doorstep.

I woke up in my foster-mother’s bed. I have no idea how I got there or when I was put there. I was there for about five days. I was drowsy most of the time, but I was aware of a beautiful, tall, well-dressed lady in the room who talked to the others but not to me.

My injuries were bandaged up and I was left alone to recover. Nobody said anything to me about what had happened. I was too scared and sick to say anything. The wounds became infected and I was very sick for many weeks afterwards.

My torn skin eventually healed.

My mind never did.

That day, my First Holy Communion day, I was damaged, utterly. Every other little girl who made her First Communion on the same day as me, in 1956, got nice presents from her loving parents and relatives. What present did I get on my special day? I was brutally raped by a monster who left me injured with a broken wrist and three broken fingers in a muddy field. I will never forget what should have been one of the happiest days of my life, but for all the wrong reasons.

I never saw the Communion dress again.

What must have been many months later, my foster-mother and I were coming out of Sunday mass in Kilmallock Church. The churchyard was packed with people but I saw her catch hold of a man tightly by the arm. When he turned and saw who was gripping him, he tried to escape. Her grasp tightened. I moved behind my foster-mother clasping the folds of her long woollen coat, as if for protection. I peered out around her, staring up at him, sick with fright.

It was the man who had raped me.

‘Ya never gave this little girl the First Communion money that ya promised her.’

‘Eh, eh, I have no change on me now at the moment. I gave my last few coppers to the collection at church.’

‘It’s not change she wants!’ she spat venomously at him, as her grip tightened painfully.

‘I’ve only a pound note on me now, for a few pints, later,’ he winced.

‘That’ll do grand,’ she said, as she leaned threateningly closer to him.

‘Aw, shag ya, there yar’ so,’ he said, with anger in his voice, as he grudgingly handed her a crumpled green-coloured pound note.

He pulled his arm from her vice-like grip and disappeared in the throng of people. She compressed the note in the palm of her hand and smiled to herself.

‘Let’s go home, Child,’ she said, as she marched off, with me shuffling close behind.

That day I was traded for a pound note.

ONE

My Foster Family

I WAS BORN, at about 6 pm, in the Sacred Heart Home for Unmarried Mothers at Bessboro, Blackrock, County Cork, Ireland, on November 14, 1948. I was premature by three weeks and my weight at time of birth was 4 lb. 12 oz. My name was registered as Celine Clifford.

In Ireland in the 1940s, when a young unmarried girl was found to be pregnant, it was impossible for her to keep living her normal life. She could not have her baby and rear her child as a single mother. The culture of the time prevented it. It was considered shameful for any young girl to get pregnant while unmarried. If one was a good Catholic parent, it was considered a slur and a disgrace on the entire family if one’s daughter became pregnant. A pregnant girl’s own people would have put her out.

To take care of such situations in the Ireland of saints and scholars, homes for unmarried mothers existed. These were institutions where a girl could have her baby, and then have it fostered or adopted, usually by Americans. Then she could rejoin some part of Irish society, but usually not in her original position, as if nothing had happened. These homes for the unmarried were places of detention, more like prisons than homes. They were a source of income for the order of nuns that lived there.

In my case, Cork Corporation paid the home £1. 2s. 6d. per baby, per week, as a maintenance fee. Bessboro was owned and run by nuns of the English Order of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and Mary. Mostly Irish women entered this Order. It was their proud boast that ‘the girls’ spiritual lives and the future of their babies were well taken care of’. I am an example of the latter and ‘my future’ was not taken care of by anyone.

Entrance to this home, was usually arranged by the clergy, at the behest of the girl’s mother. Once the pregnant girl entered through the doors she was not allowed to leave, unless strict conditions were met. After her baby was born, each girl had to stay and work for a period of three years, to help with the running of the home and self-supporting farm. During this time the babies were breastfed for 12 months. After three years, the babies were sent out to foster homes or orphanages or adopted.

The homes earned a lot of money if a baby stayed there for three years. If a girl could arrange to pay the nuns £100, which was a huge amount of money at the time, she was free to leave the home, ten days after the birth. Their babies were then immediately made available for adoption.

There was one other way of escape without the baby. If a girl’s family could arrange payment of £50, her baby would be sent to a foster home in the city, and the girl would be free to go. No girl could keep her baby or go home with her baby, no matter what her family paid.

While researching my history, a nun told me that my mother walked out the gates with me in her arms on April 18, 1949. This seems to go against the rule that no mother was allowed to leave with her baby. I have to accept that fact, but I don’t know how true it is. It is very difficult to get any valid documentation from these organisations, even now.

At that stage I would have been almost five months old. I have no idea who paid for my mother’s liberation from that place. On that same date I was fostered or ‘boarded out’ as it was known in those days. That day, my mother who had breastfed me for five months, gave me away to someone else.

As she walked away, she closed her heart to me, for ever. Every baby smiles when being held by its mother. I wonder if we ever bonded as mother and daughter.

As a total coincidence, on that same November 14, 1948, another young mother was giving birth to her first child, in somewhat better circumstances, at Buckingham Palace in London. Her name was Princess Elizabeth Windsor. The Princess named her precious newborn son, Charles Philip Arthur George.

For two people who were born on the same day, we would be fated to lead vastly different lives. His to be one of absolute privilege, mine to be one of utter deprivation.

An extremely poor, old-aged, childless couple, who lived in a remote area of County Limerick, fostered me. The fostering arrangement was made through Limerick County Council as my foster-parents had already done a bit of fostering. I had a foster-brother living in the house with me. I don’t know what age he was when I arrived, but he had a terrible time. My foster-father used to beat him so hard, for no reason at all, and they would lock him in a room for days. I remember trying to hide bread and give it to him because he was starving. I felt so sorry for him. When I got a bit older I didn’t see him so much because he was working.

We lived in what was then called a cottage, but would be better described as a shack. It consisted of two rooms, a large central room with a small bedroom at the end. There was a tiny porch-sized area, attached at the rear of the building, where turf for the fire was kept and through which access was provided to the backyard. The roof of the main building was rough slate. From inside you could see the rough wooden beams, holding sods of clay that were packed close to the stone as soundproofing against the monotonous din made by the incessant Irish rain. The central room had a large fireplace, and this was where almost all of the daytime and night-time social gatherings took place. The house was built on about an acre of land.

I later discovered that a Catholic priest, a nun and a medical doctor, who were all close friends of my grandmother, on my mother’s side, were instrumental in making arrangements for this fostering. I was now to be called Celine O’Brien.

By the time I arrived, my foster-mother was in her sixties and her husband was perhaps ten years older. They were a totally unsuitable couple to foster a five-month-old baby girl. But nobody cared. If abortion had been available, I would have been a prime candidate. Everyone wanted me out of his or her world. Alive, I was an embarrassment to everyone.

No One Wants You

No One Wants You